本展覽發展出5個分區:

The exhibition is developed with 5 sections:

I. 從全球到邊緣 (FROM THE GLOBAL TO THE MARGINAL)

刺青是人類無法磨滅的遺產。在歐洲,此項習俗受到基督教的壓抑,直至19世紀仍是作為罪犯的標示而存在。另一方面,自15世紀大探險時代,西方旅者在亞洲、大洋洲、美洲(再度)發現刺青,但刺青卻僅能在水手與冒險者的皮膚上遊走,失去其在歐洲以外社會所具有的同化功能。在各個殖民地中,殖民政府則強力禁止傳統的刺青習俗。這項全球性的習俗始終退居在社會邊緣。但在19世紀初的歐洲,刺青轉化為表達個體性的地下語彙,以千變萬化的個人風格,匯聚成抵制主流的實際行動,讓刺青的邊緣化特質成為一種宣言,並再次散播流傳,感染了街頭、監獄與表演藝術圈。

An indelible legacy, tattooing belongs to the common heritage of most of humanity. In Europe, the practice was repressed by Christianity and, until the 19th century, it principally persisted as a means of marking criminals. However, from the 15th century, during the period of great explorations, tattooing was (re)discovered by Western travellers in Asia, Oceania and the Americas. Journeying almost exclusively on the skin of sailors and adventurers, the tattoo lost the assimilation function that it fulfilled in societies outside Europe. In the West, this global practice settled into the fringes of society, while in the overseas territories, the colonial authorities actively repressed the traditional practice of tattooing for religious, magic and initiation purposes. At the start of the 19th century in Europe, tattooing, henceforth a matter of choice, became the underground language of a kaleidoscope of individualities brought together around a practice defying generalization and laying claim to its marginalization. Tattooing once again spread. It contaminated the street, the prison world, as well as a milieu marked by widespread eccentricity: that of the performing arts.

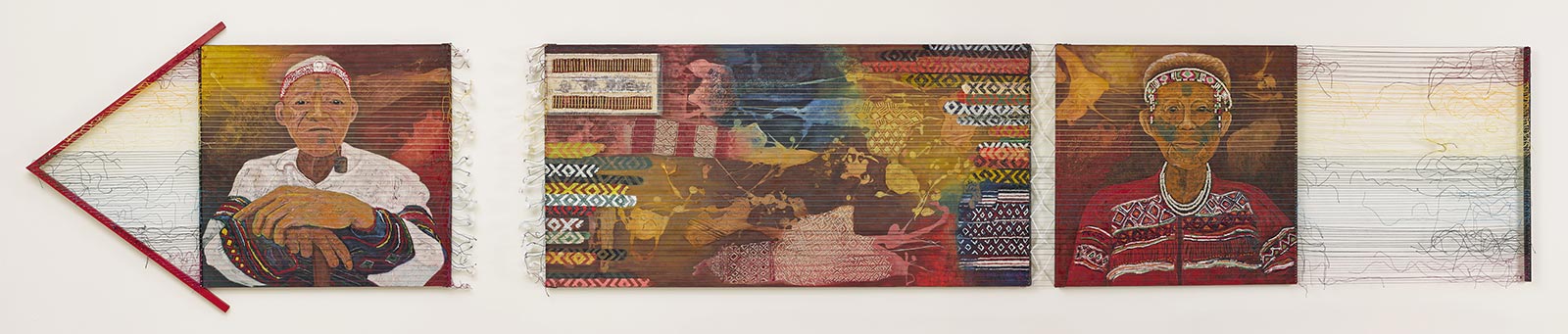

高雄市立美術館典藏

© 安力‧給怒 / 高雄市立美術館

Broken Arrow 2015. Anli Genu (1958- ). Mekarang, Atayal tribe, Hsinchu, Taiwan. 2012. Oil on canvas, flaxen thread, wood. 110 x 567 cm

Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts (Inv. 04294)

© Anli Genu / Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts

II. 運轉中的藝術 (ART IN MOTION)

如果刺青得以成為一種藝術表現的形式,可歸功於歐、亞、北美一群在技術與藝術價值上積極創新並相互交流的刺青藝術家。1891年,美國人奧瑞利(Samuel O’Reilly,?-1908)發明電動刺青機,大幅增進刺青的發展與傳播。美國刺青的興盛,還可歸因於對日本「入墨」(irezumi)觀察,讓20世紀期間太平洋兩地的刺青藝術家形成熱烈的國際對話。在英國,刺青藝術家沿襲了日本刺青客自1902年起集結成社的模式,並於1953年在布里斯托(Bristol)成立了第一個刺青俱樂部。美國則於1976年在休斯頓(Houston)首次舉行國際刺青大會,歡迎來自全球的刺青藝術家與刺青客共襄盛舉。這些聚會象徵了刺青正開始邁向全球性的重建。

If tattooing emerged as a form of artistic expression, it was thanks to the circulation of practices between tattoo artists in Europe, Asia and North America, interested in technical and artistic innovations. In 1891, the invention of the electric tattoo machine by the American Samuel O’Reilly(?-1908) considerably increased the possibilities of tattooing and favoured its dissemination.

The effervescence of American tattooing owed a great deal to the observation of the Japanese irezumi: American and Japanese tattoo artists travelled from one shore of the Pacific to the other to trade their secrets. During the 20th century, the international dialogue between activists grew stronger. Following the model of tattooed Japanese who gathered in societies from 1902, tattoo artists got together in clubs, the first of which was created in 1953 in Bristol, in the United Kingdom. The first international tattooing convention, held in 1976 in Houston, in the United States, welcomed tattoo artists and tattooed from the entire planet. These meetings marked the beginning of the global reconstruction of tattooing.

© 法國國家凱布朗利博物館;攝影:克勞德‧傑曼

Tattoo project: body suit – Rinne, Dojo, Ji. Shige (1970- ). Japan. 2013. Painting on linen canvas. 120 x 80 cm

© Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris, photo Claude Germain

III. 脫胎換骨:傳統刺青的復興 (MAKEOVER: REVIVAL OF TRADITIONAL TATTOOING)

在日本以外的亞洲與大洋洲,刺青自18世紀起由於受到殖民化、基督教化與社會變革的綜合影響而被大幅遺棄,除了極少數的島嶼之外,刺青及其相關習俗都衰退沒落。自1980年代起,透過旅行的刺青藝術家,原住民的刺青從業者迎來了國際性的客戶群,以及來自各種師學淵源,且富有理想與抱負的刺青藝術家,他們一心一意要振興這些古老的傳統。我們目前正見證著一場空前的傳統刺青復興大業。全球化且活力充沛的薩摩亞島(Samoan Islands)正是此項復興事業的技藝核心與參考重點。

In Asia – apart from Japan – and Oceania, tattooing was very much abandoned from the XVIII century under the combined effects of colonization, evangelization and changes in the societies. With the exception of a very few islands, tattooing and the customs with which it was associated fell by the wayside. Starting in the 1980s, through travelling tattoo artists, indigenous practitioners met an international clientele and aspiring tattoo artists from every origin, clearly bent on reviving these ancient traditions. We are currently witnessing an unprecedented renewal of traditional tattooing. Globalized and very dynamic, the Samoan Islands are its centre of expertise and reference point.

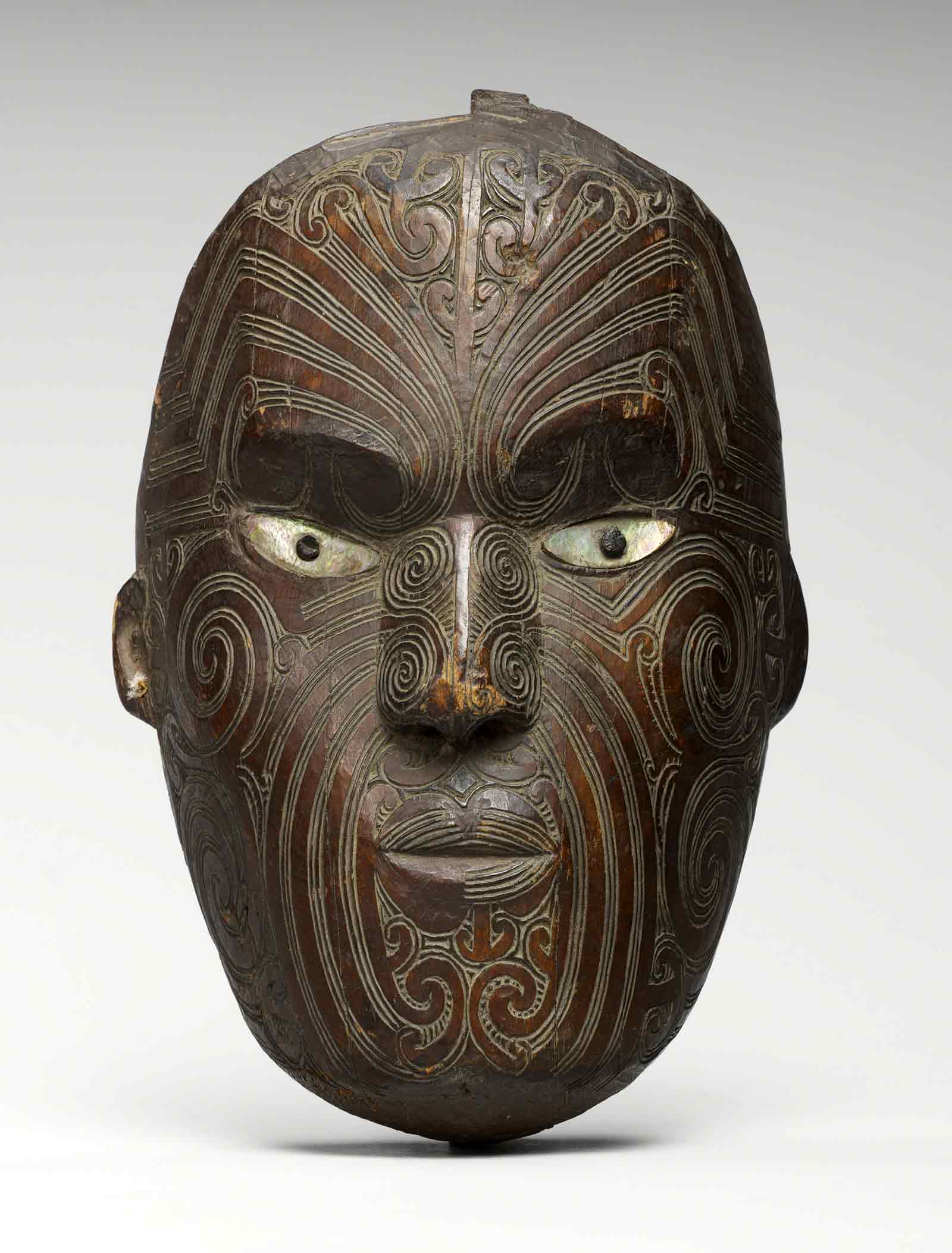

法國國家凱布朗利博物館典藏

© 法國國家凱布朗利博物館;攝影:蒂埃里‧奧利維爾、米歇爾‧烏塔多

Koruru or Parata (gable mask). New Zealand. 19th century. Carved wood, white pigment, pāua shell. 27 x 18 x 14.5 cm

Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris (Inv. 71.1959.71.1)

© Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris, photo Thierry Ollivier, Michel Urtado

IV. 世界的新版圖 (NEW TERRITORIES OF THE WORLD)

具藝術能量的標竿人物突顯出當代刺青的進化特質,新的流派正持續不斷湧現。1977年,刺青藝術家卡特萊特(Charlie Cartwright)與魯迪(Jack Rudy)推翻了細節與陰影技法表現的限制。這項流傳於洛杉磯幫派中的獨特寫實風格技法,從墨西哥裔美國人特有的奇卡娜(chicana)文化中那些源自美、墨兩地精緻與流行文化的圖案語彙裡汲取主題。在中國與台灣,刺青自2000年代起再度興起,刺青師們的靈感來自娛樂產業中的流行文化及充斥其中的影像(漫畫、電玩、電影),也來自廣褒浩瀚的中國歷史圖像遺產。在歐洲,於此同時,抽象與書寫形式則成為探索某一特定前衛風格的主題與材料。

Markers of the artistic dynamism characterizing the evolution of contemporary tattooing, new schools are constantly emerging. In 1977, the tattoo artists Charlie Cartwright and Jack Rudy pushed back the limits of detail and shading. This specific technique of the realistic style of Los Angeles gangs draws its subjects from the chicana culture with its graphic vocabulary taken from American-Mexican learned and popular cultures. In China, from the 2000s, the practice of tattooing has re-emerged. Its practitioners find inspiration in both the pop culture of the entertainment industry with its flow of images (mangas, video games, cinema) and the vast heritage of Chinese historical iconography. In Europe, at the same time, abstraction and the graphic form have become subjects and materials to explore for a determined avant garde.

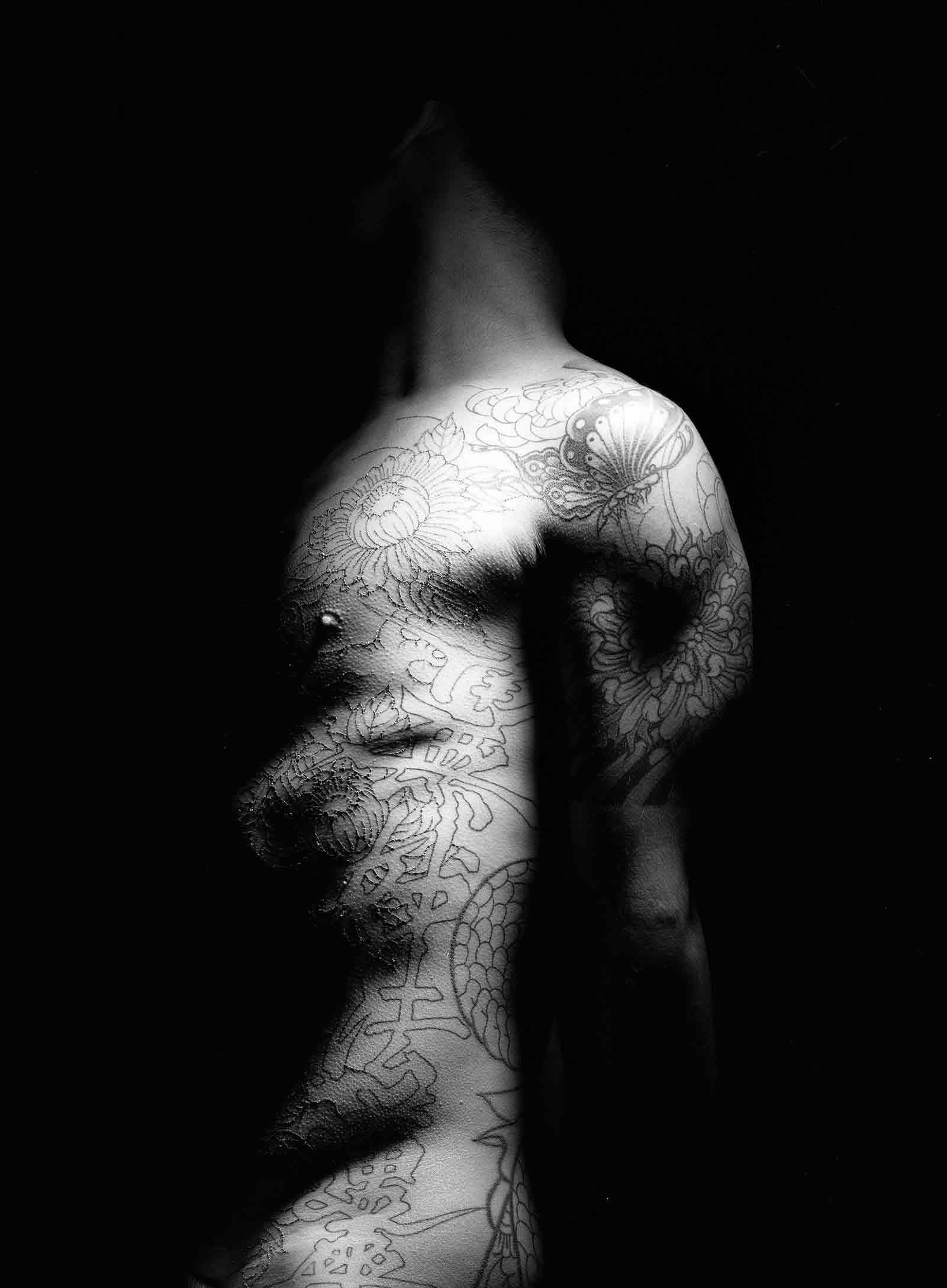

高雄市立美術館典藏

© 高媛 / 高雄市立美術館

Gangster 1, The chronicles of tattoo in Taiwan series. Gao Yuan (1958- ). Taiwan. 1990. Photograph: print on black-and-white photographic paper. 136 x 100 cm

Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts (Inv. 03940)

© Gao Yuan / Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts

V. 今日刺青 (TATTOO NOW)

隨著刺青藝術家賓尼(Alex Binnie)、柯利(Curly)及勒黒(Xed LeHead)等以新風格帶領刺青邁入第三個千年。今日刺青可分為兩派:有些是重新詮釋歷史題材,偏好日本「入墨」風格,或美國舊式派別、俄國古拉格監獄刺青的粗放脈絡,或歐式的「生澀」(brut)線條。另一派則形塑了跳脫現有規範的美學,探索與平面藝術連結的可能性,以文字造型、影像畫素、框格與圖表創造出另類主題,呈顯新的構圖,也愈形抽象。若說後者的藝術哲學並未直接奠基於前輩大師們的遺產,前者仍受到過往的影響。不論如何,兩種流派在過去10年來已表現無以撼動的決心,致力革新刺青及其規範,並提出新的美學概念。

Following the styles launched by the tattoo artists Alex Binnie, Curly and Xed LeHead, a new generation has brought tattooing into the third millennium. Two schools can be discerned nowadays: some tattoo artists reinterpret historical genres, preferring to the Japanese irezumi, or to the American old school, the wild vein of Russian gulag tattooing or the European “brut” line. Others formulate aesthetics that are freed from current codes to explore the possibilities linked to graphic arts, in which typography, pixels, frames and diagrams bring out other motifs and compositions appear, going as far as abstraction. If the latter school does not directly base its artistic philosophy on the legacy of the great master tattooers, the former remains influenced by the past. However, both schools, during the last decade, have expressed an unshakable determination to renew tattooing and its codes to propose a new aesthetic.

法國國家凱布朗利博物館典藏

© 法國國家凱布朗利博物館;攝影:托馬斯‧杜瓦爾

Tattoo design on a female arm. Yann Black (1973- ). Canada. 2013. Ink on silicone. H 71 cm

Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris (Inv. 70.2017.26.1)

© Musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac, Paris, photo Thomas Duval